|

Eager Space | Videos by Alpha | Videos by Date | All Video Text | Support | Community | About |

|---|

You might already know the story...

With the completion of the international space station, the landing of Atlantis at the end of the STS-135 mission marked the end of the space shuttle program.

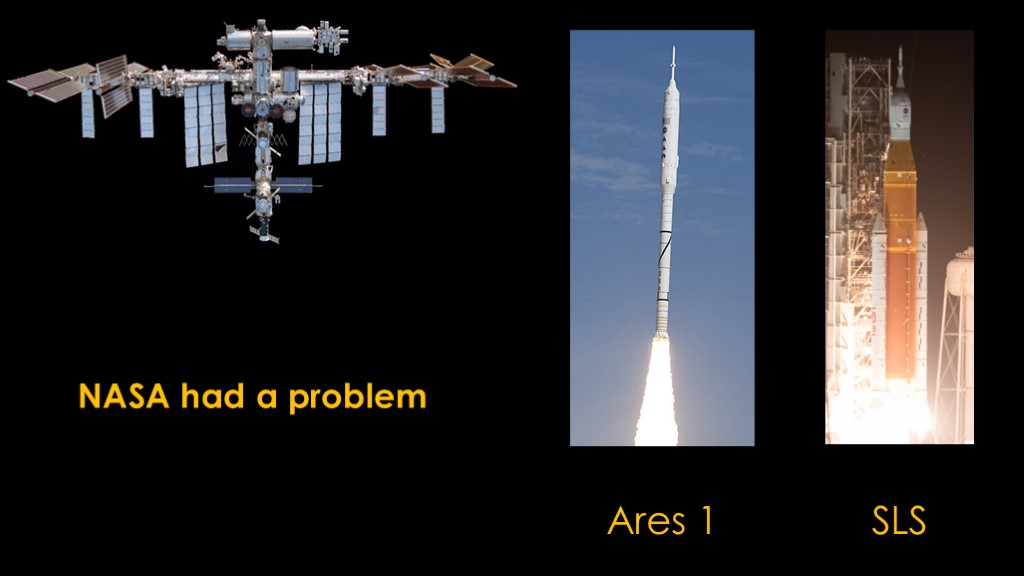

That left NASA with a problem. The only way to fly astronauts to the space station was on the Russian Soyuz, and that both limited the number of astronauts on the station and made NASA look bad.

There had been a plan to launch astronauts on the Ares I launch vehicle as part of NASA's Constellation program, but that was cancelled in 2010 and the follow-on Space Launch System was not a viable option because it wasn't ready and it would be an extremely expensive option to get to the space station.

Traditionally, NASA had a very particular view of the spaceflight world...

We fly people, and they fly cargo.

NASA worked hard to keep their monopoly on human spaceflight in the US, but with the shuttle program over and nothing on the near horizon, NASA opted to redefine what "we" meant and the commercial crew program was created.

After some up-front development work, NASA selected proposals from two companies.

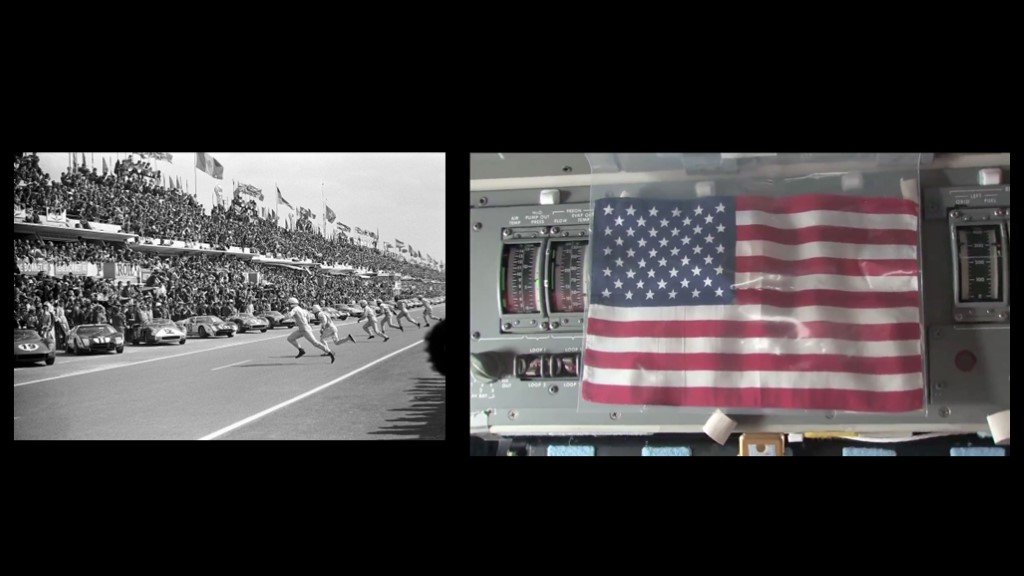

With the awarding of those contracts, the race was on.

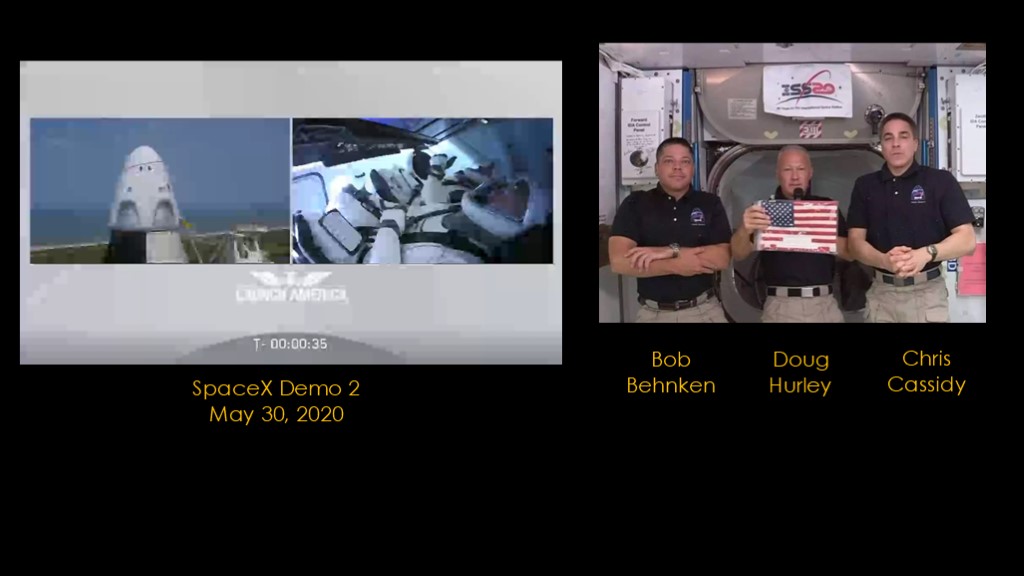

There was even a prize - this American flag was flown on the first shuttle mission in 1981 and the last shuttle mission in 2011 and was left on the international Space Station to be "captured" by the next astronauts to be launched to the ISS from North America.

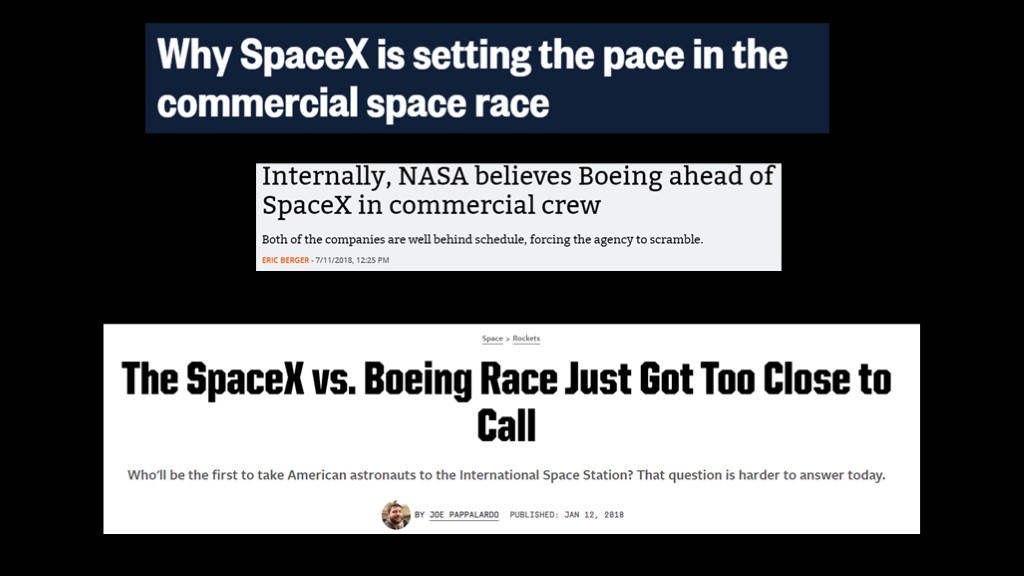

It was an interesting time...

Depending on who you listened to, Boeing was ahead, SpaceX was ahead, or the race was too close to call.

Finally, on May 30, 2020.

SpaceX Demo 2 took astronauts Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley to the ISS where they claimed the flag, narrowly beating the Boeing Starliner team.

Or so we thought...

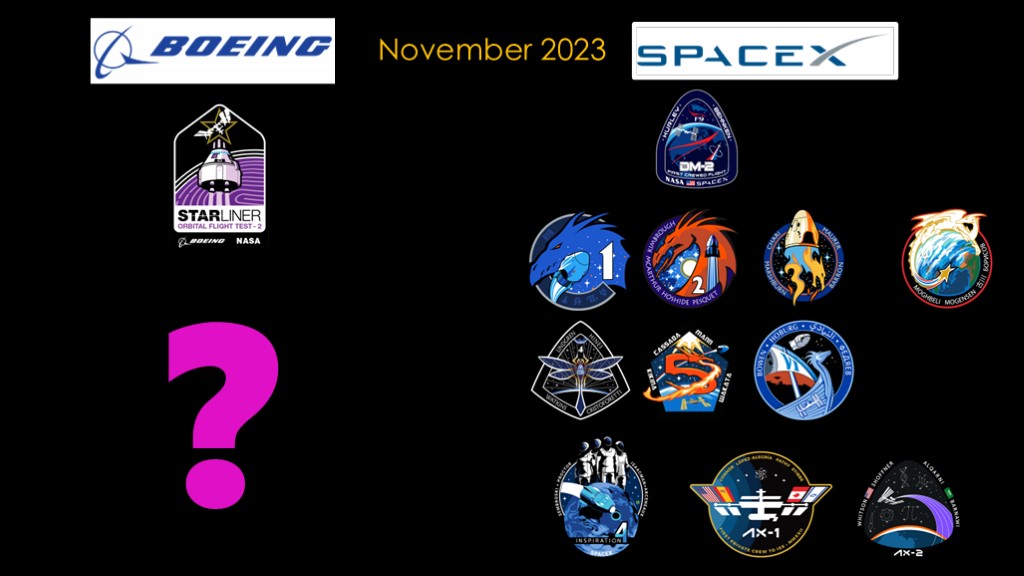

It's now November 2023

SpaceX flew the first crewed mission to the ISS in 2020

They have since flown all 6 of the missions contracted for in the original commercial crew contract and the first of 8 additional missions purchased by NASA.

In addition, crew dragon flew the inspiration 4 free-flying mission and two Axiom Space missions to the ISS.

That's 11 crewed missions carrying 42 passengers.

Starliner flew once in 2022, successfully docking with the international space station on their second orbital flight test and setting the stage for their first crewed flight.

What the hell happened to Starliner and what does the future look like?

We'll start with the first part, and begin by looking at Boeing...

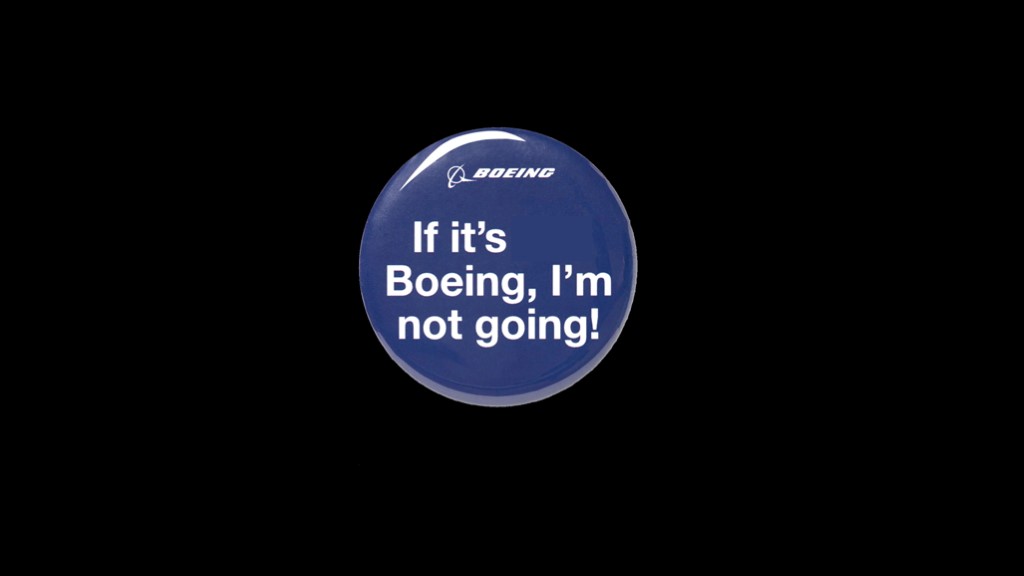

I grew up in the Seattle area and worked for a few years for Boeing Computer Services out of college.

At the time, Boeing made great products and this was a common sentiment when travelling.

But since the merger with McDonnell Douglas, they haven't been the same company.

There are a bunch of different theories about why the Starliner delays are Boeing's fault and it's worth the time to examine a few.

One idea is that boeing bid on commercial crew believing that SpaceX would fail and they would later be able to extract more money from NASA.

There's certainly some truth here - in 2016 Boeing proposed higher prices for flights 3-6 of their 6-flight contract which NASA rejected as they did not align with the prices Boeing had given in their original contract proposal.

NASA made a counter-proposal, and eventually ended up agreeing to pay an extra $287.2 million towards their commercial crew contract.

When this was revealed in 2019, Boeing's response was this (read).

Yes, they got extra money for those missions to ensure that missions 3-6 would be ready to fly on time.

I'm going to vote "yes" for this assertion since Boeing did extract the promise of more money from NASA.

The idea here is that Boeing did not understand the world of firm fixed price contracts.

I have long asserted that companies are designed to do specific things and operate in specific markets. For example, ULA was created specifically to sell expensive launches to NASA and the department of defense.

I think Boeing got confused by the early part of the program, where they received $580 billion in space act agreements, which you can think of as being very much like the cost plus world that Boeing is comfortable in, and presumably Boeing spent a lot of this money coming up with a plan that they believed they could execute on.

They then signed the firm fixed price contract, one that would only pay them at specific milestones.

My confidence in this theory is high, because Boeing very recently admitted that they are struggling to make money on firm fixed price contracts for satellites, for the KC-46 refueling aircraft, and for Starliner.

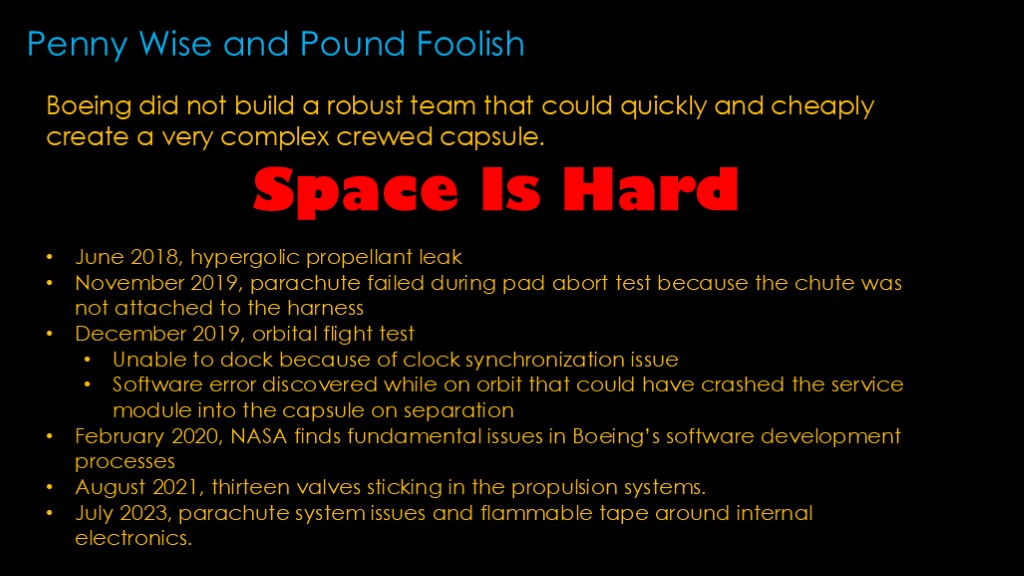

Many people assert that Boeing did not build the right kind of team and spend the right amount of money to build a crewed capsule.

We frequently hear that space is hard, but the real question is whether the issues you are running into are ones you should have found or are you finding new and innovative ways to fail.

I could not find a definitive list of Starliner issues but if we look at this list, it's quite damning - if your QA is missing issues like the parachute problem or the orbital flight test software issues, there's a case to be made that you have no business developing a crewed space vehicle.

This is clearly one of the big problems, and perhaps the major problem.

I also suspect that Boeing came to the wrong conclusion about SpaceX's success with cargo dragon

The right conclusion is that cargo dragon is a fully functional and robust capsule that SpaceX developed quickly and therefore they have a head start on getting a commercial crew capsule done.

That means that Boeing would need to up their game to keep up with SpaceX.

Unfortunately, their conclusion seems to have been "SpaceX did it so capsules can't be very hard".

Those are the main issues where I think Boeing is directly responsible. But there were some other issues that they had less control over...

One unappreciated cause of delays is scheduling complexity, and that comes from the design of the international space station and a specific decision that NASA made.

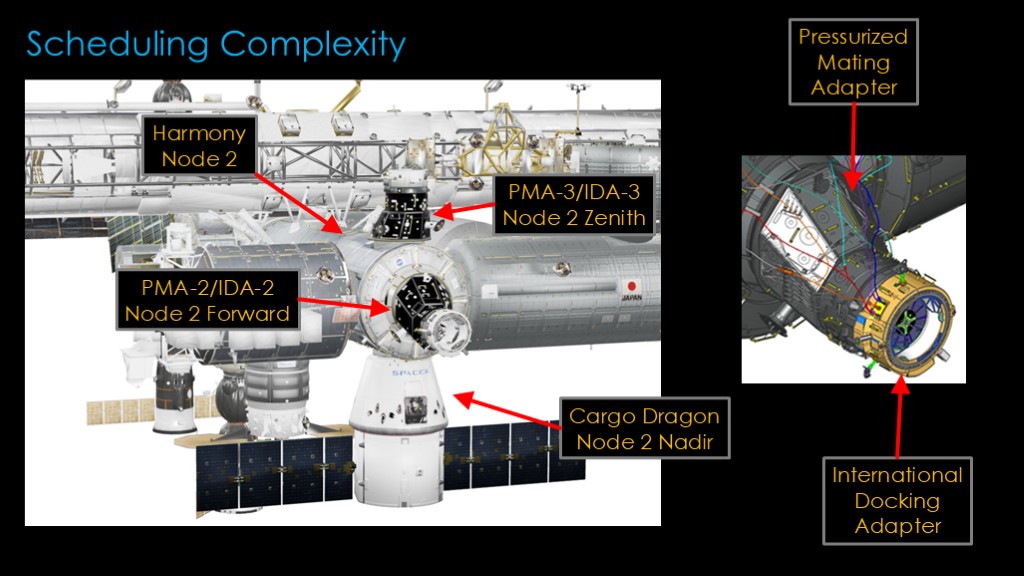

This is a view of the ISS, showing us the harmony module also known as node 2.

At the part of the station facing the earth - or nadir side - there is a SpaceX version 1 cargo dragon. These cargo dragons did not dock with the space station, they were berthed - or attached - to the space station using the robotic arm.

Docking is more complicated.

Station uses a pressurized mating adapter to connect US and Russian segments and this was also where shuttle docked. After shuttle, NASA came up with the international docking adapter which connects to the PMA to support the new international standard.

Node 2 supports two of these adapters, one on the zenith or top port, and one on the forward port. You might see them referred to either as a PMA or an IDA.

If you're curious about the numbering, IDA-1 was lost during the SpaceX CRS-7 launch failure.

These adapters are the only places where commercial crew capsules can dock.

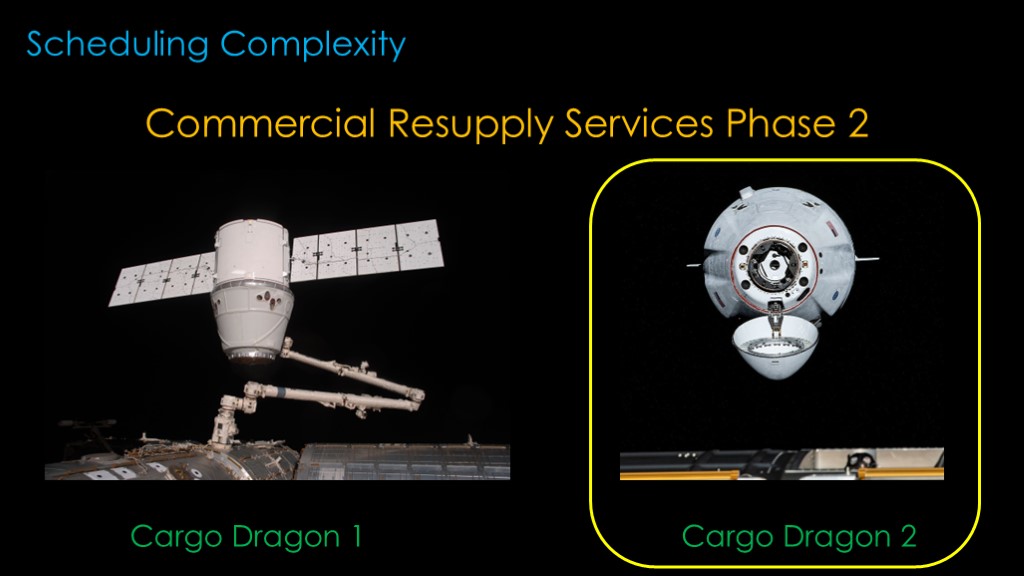

For the second phase of commercial resupply services, SpaceX gave NASA two bids...

SpaceX could keep flying the existing cargo dragon, or SpaceX could fly a cargo variant of the Dragon 2 that was being developed for commercial crew.

NASA chose the updated version.

The outcome of this decision was that there was now another vehicle that could only dock to those two ports.

Let's see how that impacts scheduling.

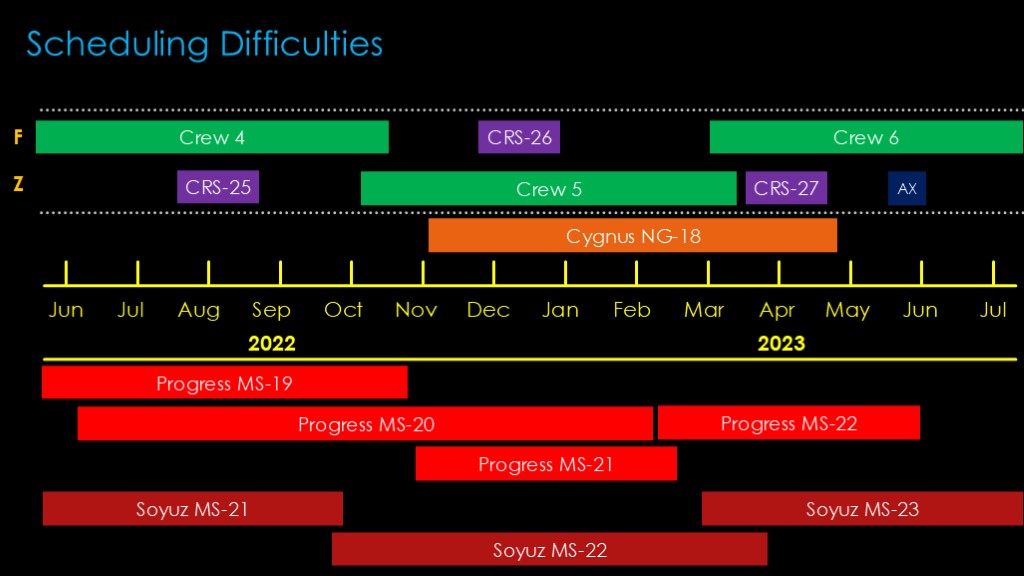

There are two ports on node 2, and here's how they were occupied with crew flights during this time period. There's roughly a week overlap where both ports are full, but there appears to be lots of empty space for Starliner test flights

There are, however, short visits of cargo dragon in those open time slots, and those are busy times on station because the astronauts need to prepare cargo to return to earth, unload and reload dragon, and then do whatever needs to be done with the new cargo.

There also may be short Axiom commercial visits that take up a port for a week or so.

To further complicate scheduling, there are Cygnus resupply flights. They do not take up a crew docking port, but they still require scheduling and planning.

Add in the Russian progress resupply flights and the Soyuz crewed flights - both of which impact everybody on the station - and it becomes clear that scheduling is very complicated. Starliner is not making operational flights, so it has lower priority and NASA can only give it limited windows to visit station. If there's a slip, the next open spot may be many months in the future, and therefore there are no small slips for Starliner.

SpaceX didn't have this problem with crew dragon as there was always an open port they could use and NASA really wanted crew flights as soon as possible. And it won't be an issue when starliner is operational as they will alternate flights with crew dragon. But it does cause delays now.

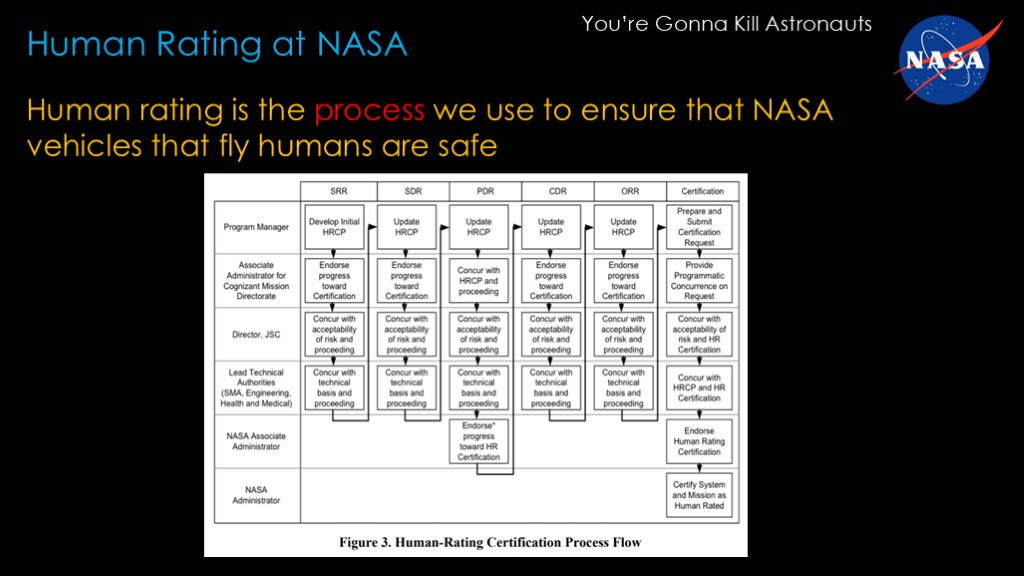

NASA has long had a somewhat strange approach to crew safety. For a detailed discussion, see my video "You're gonna kill astronauts - reliability and crew safety at NASA".

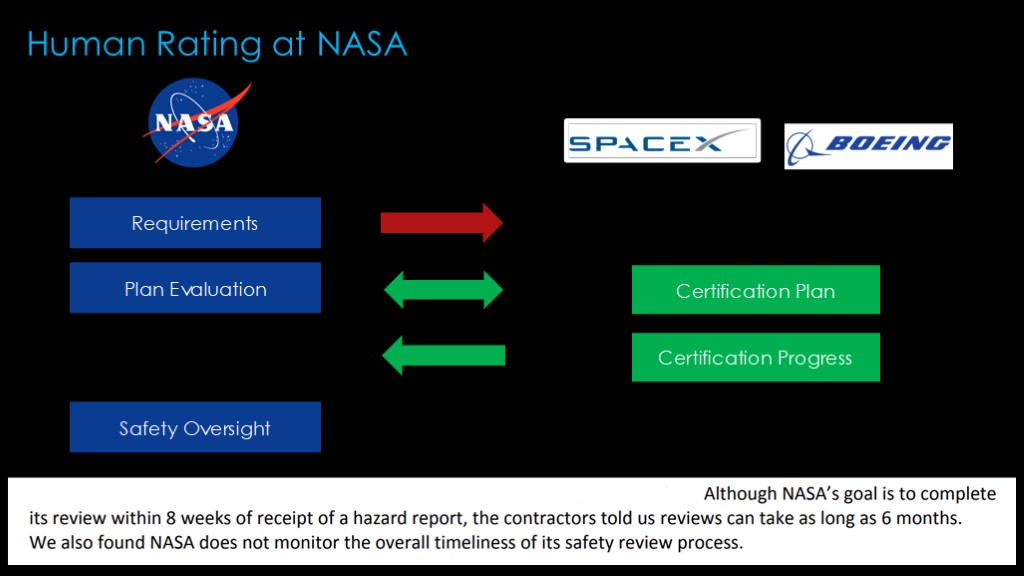

For the sake of this discussion, I think this is a fair description of how NASA views human rating - NASA has a process that they follow and at the end a human-rated system pops out of the process. Here's an *overview* of the entire process, and of course each step is long and involved.

With commercial crew, however, the goal is to be more contractual. The model is that NASA will send requirements to the contractor, and then the contractor will define a certification plan that details how they will verify that they meet those requirements or waiver requests detailing why it doesn't make sense for them to meet a specific requirement. After some back-and-forth, the certification plan is approved.

The point of this approach is to allow contractors the flexibility to choose the verification approach that works best for them. For example, SpaceX chose to perform an actual in-flight abort test for crew dragon, while Boeing chose to verify that ability through analytical methods.

During development, the contractor sends information about their progress and NASA maintains safety oversight over the program as a whole.

This seems like a reasonable approach, but there are a few problems.

The first is that at the time that SpaceX and Boeing bid on the commercial crew program, the requirements didn't actually exist. NASA was forced to go with the commercial option and they weren't prepared ahead of time. In some cases, the NASA requirement was aspirational - they settled on a reliability requirement of 1 loss of crew event in 270 flights without determining whether such a requirement was achievable.

NASA was also unprepared to review the certification plan and the hazard reports generated by the contractors. NASA's goal was to complete reviews within 8 weeks but the contractors had to wait as long as 6 months for some reviews. NASA did not monitor the timeliness of these reviews.

The slow responsiveness of NASA stretched the timeline directly and also increased the chance that their response would require costly rework later in the cycle.

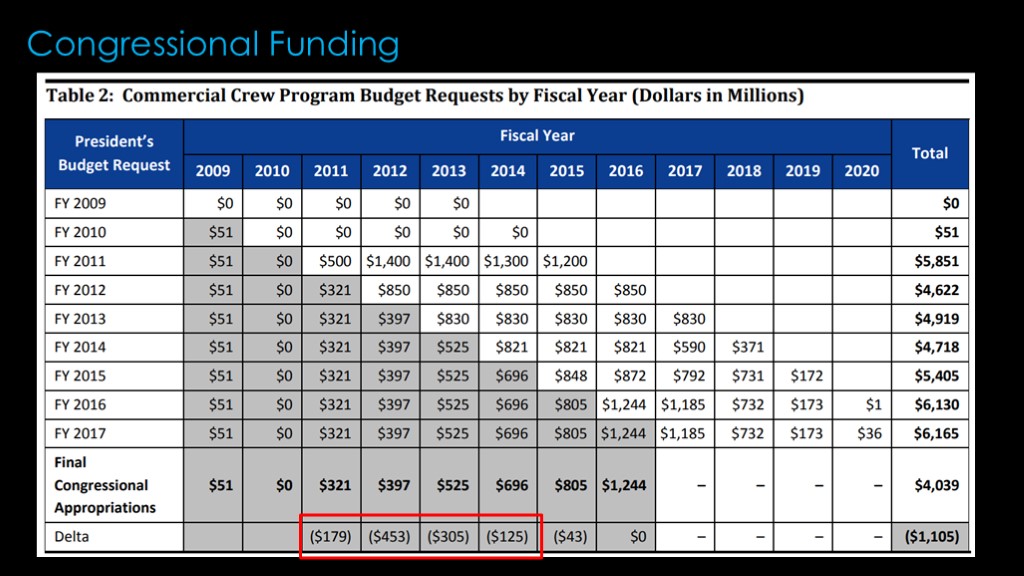

Congress chose to underfund commercial crew.

This somewhat confusing chart from NASA's inspector general report shows the details.

For the four years indicated, congress provided significantly less funding than NASA requested, providing $1.9 billion instead of the $ 3 billion NASA requested. This had a significant effect in slowing the program down, especially in slowing down NASA's ability to move quickly early in the program.

There was a covid-19 effect

Boeing has 425 suppliers across 37 states involved with Starliner, and when the COVID-19 pandemic hit their ability to get what they needed was disrupted.

SpaceX doesn't give out supplier data but they are well-known for doing much of their work in house and that left them less vulnerable to disruption.

And now for the question many people are asking...

Why hasn't Boeing cancelled starliner?

Let's look at some possible explanations...

Prestige is a factor; Boeing views itself as a big player in defense and space and having failed at a crewed capsule would reduce their prestige.

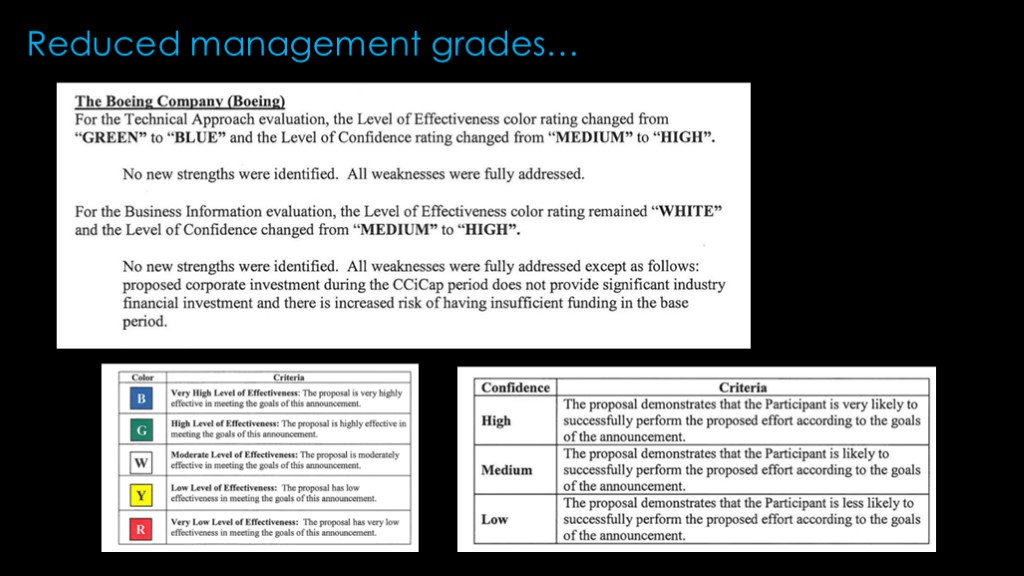

All government bidders get ranked not only price but on their capability to execute on projects successfully. Boeing got high grades on their commercial crew proposal and that made it easier for them to get a contract.

Cancelling Starliner would make it harder for them to win future contracts as it would their management grades.

There is a possibility that Starliner can garner additional business.

The real reason comes down to money. Continuing with Starliner appears to be the best decision monetarily.

I'll get into why in a moment, but I want to address two related questions first.

The first is whether Boeing made the right decision to sign the commercial crew contract, and it's pretty clear that this point that Boeing thinks the answer is "no". They have sworn off firm fixed price contracts.

Will they make a profit off of starliner? They clearly have not made a profit *yet* and it's probable they won't, though profit is still possible.

But neither of these questions is the right one to ask at this point.

Those questions are looking backwards. They are interesting from an analytical standpoint but they aren't useful in figuring out what to do in a specific situation. They need to be looking forward.

The question they are asking - and have been asking throughout the delays - is whether there is a good chance that going forward will result in useful amounts of net cash?

And it's pretty clear that Boeing still thinks that is true. And here's why...

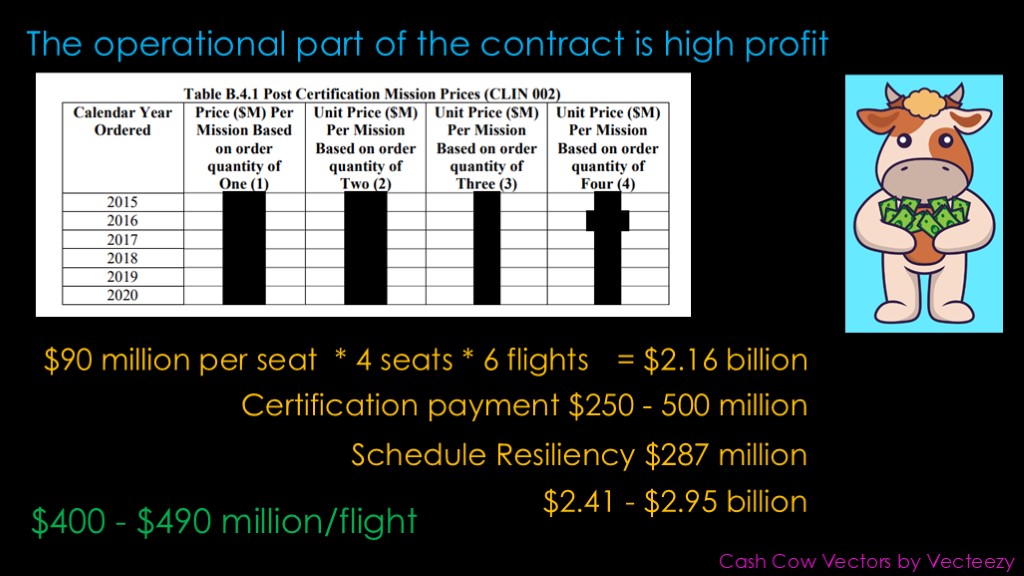

The fact is that the operational part of the starliner contract is a cash cow...

If you look at the commercial crew contracts you'll find that much of the interesting information - including monetary amounts - has been redacted, but there's also this pattern of either NASA's office of the inspector general or the general accounting office releasing some of that data.

The OIG estimate was that the starliner cost per seat was $90 million. Each capsule carries 4 astronauts and Boeing has a firm contract for 6 flights, so that's $2.16 billion for those 6 flights.

That is a lot of money, more than half of the total amount of the contract.

And it's actually more than that.

There is the payment that Boeing gets when they successfully complete their demo mission to the ISS. We don't know how much that is, but it is likely substantial, probably somewhere in the $250 - $500 million range.

It's also possible that the $287.2 million dollar increase Boeing negotiated for some flights is not included in the $90 million estimate.

That yields an overall estimate at somewhere between $2.41 and $2.95 billion total, or $400 - $490 million per flight.

That is why Boeing has been absorbing losses along the way and still going forward - the contract is specifically designed to put the profit in the operational phase and give the contractors a big incentive to get there. And NASA putting in a firm order for all 6 flights made the possible money bigger.

Boeing may not make a profit on the project overall, but their cash flow situation will be much better with $2 to 3 billion in revenue from it than with zero revenue. At least that's what they're betting.

If you enjoyed this video, please send me a Boeing CST-100 Starliner Air Brush Quarter Zip Shirt, size medium, on sale at only $37.99